Grandmother Portrait

Most of us have experienced, or at least can comprehend, the burning sting of loss when something precious to us is harmed. Perhaps you are the custodian of a treasured family heirloom that has fallen into disrepair or the proud purchaser of an artwork that has suffered unfortunate damage. The frustration we face when confronted with a much-adored but deteriorated piece of art can lead us to believe that the appearance it once had could never be restored. The artwork has been negatively impacted by time and circumstance, and something very important about it might seem lost to us and future generations forever.

When approached by clients facing this problem it is common for conservators to hear the phrase “Is this beyond repair?”. Realistically, there are instances when damage to an artwork may be too complex or permanent to resurrect it to a point at which the appearance is in harmony with the artist’s original intent. However, this is rare, as professional conservators are trained to be able to use a great plethora of unique and highly skilful techniques that can successfully, safely and authentically conserve, preserve and restore even extensively damaged artworks.

A pertinent example is the 1913 portrait of Boonah resident Kathleen Byrne. Kathleen was the much-beloved grandmother of a Studio 204 client. The portrait was painted when Kathleen was a debutant to a long and fulfilling life. Here she is depicted at the tender age of 18, yet to marry her husband Ernest Zurvas, bear no less than eight sons and go on to become a Railway Station Mistress at Teviotville. As the daughter of an Irish firefighter, a mother of eight children and a working class woman who seemingly lived with moderate economic security, Kathleen’s purposeful yet no doubt tiring life carried forth the legacy of her immigrant father. The courageous, and rough and ready spirit of a firefighter would have been a great match for the turn of the 20th century popular Australian ethos of comradery, group solidarity and disregard for traditional manners, which had its roots in the bush folklore forged by the early convict, working class and Irish born settlers. Together with its youthful subject immersed deep in somber thought, its tasteful yet unpretentious fashion and furnishings and the distinctly Australiana landscape depicted within the painting itself, this artwork speaks strongly of a respectable yet tough life yet to be lived in the brave new world of post-Federation Australia. It is no wonder that this painting would have both great sentimental value and social significance to the client who brought it into the studio.

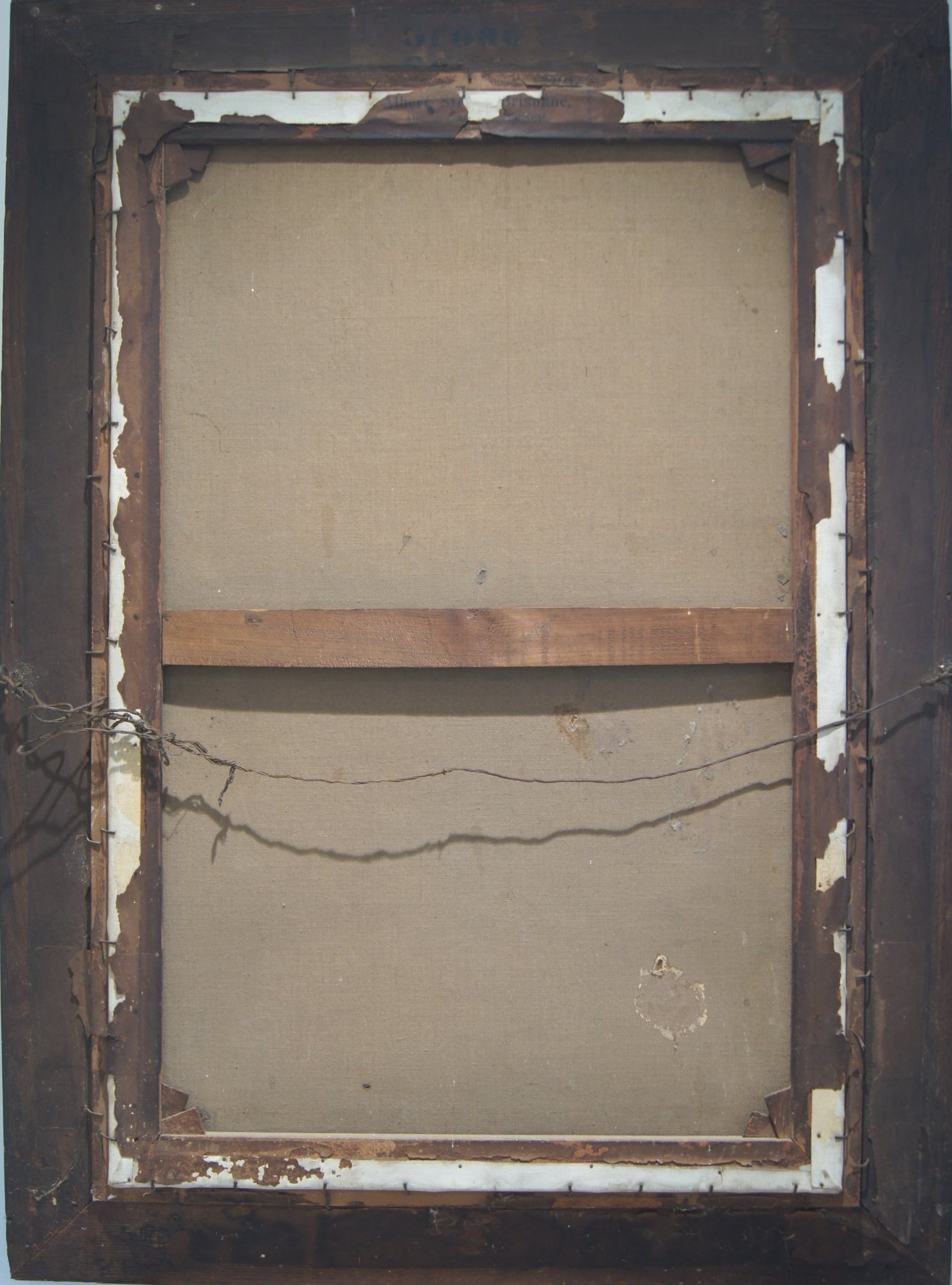

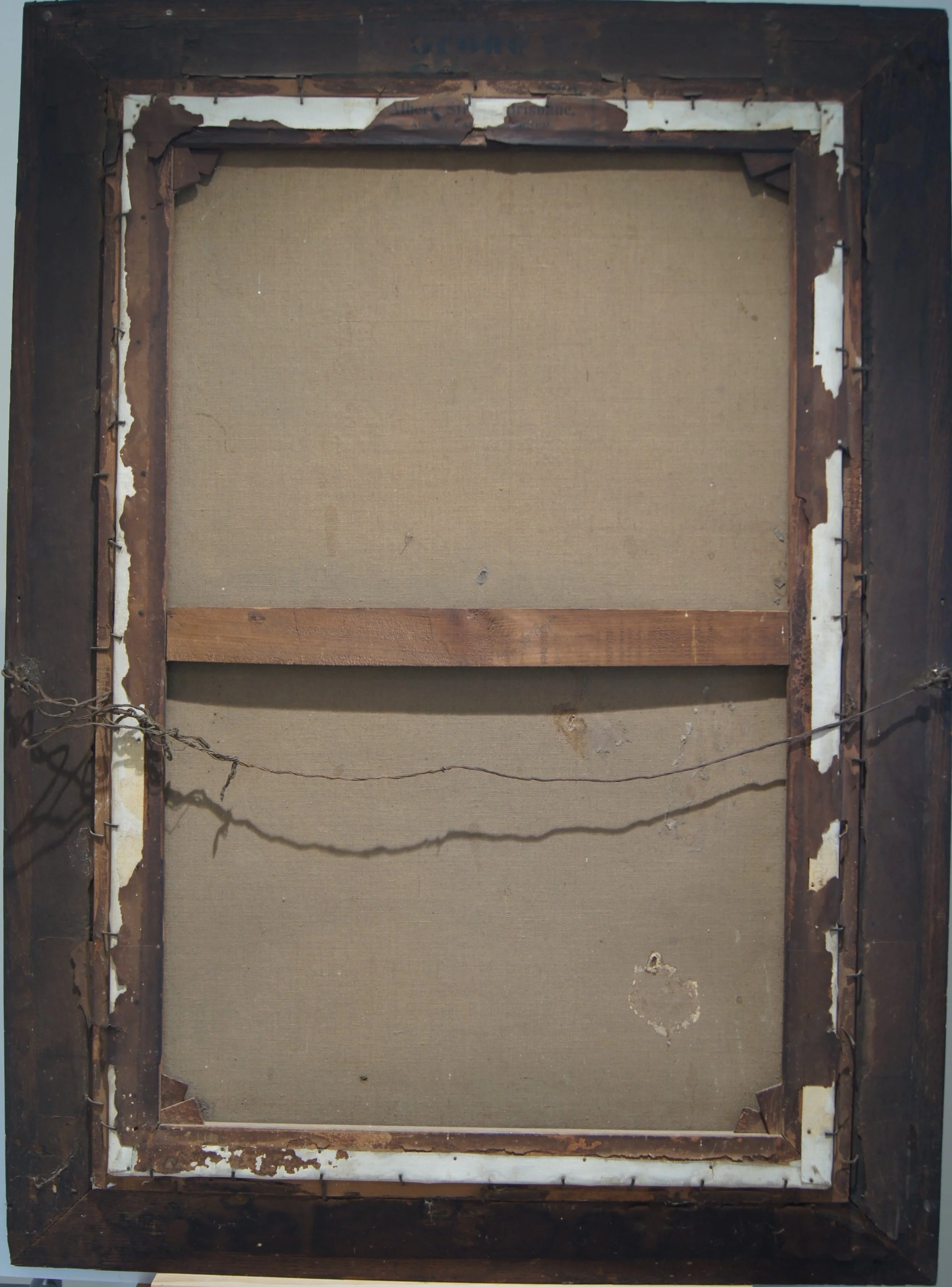

Understandably he was very dismayed that the painting had suffered extensive damage. It was not surprising that the question arose “Is it possible to fix this?”. The hundred-year-old oil painting had suffered from significant dirt and frass build-up (excrement and other debris caused by insect activity), several holes and tears in the canvas, discolouration of the oxidised varnish, deterioration of original painting labels, damage to the frame and, most concerningly, severe crazing to the paint layer. Crazing is the technical term for the cracking of paint, and it usually occurs when an upper paint layer has dried considerably more than an underlayer of paint, gesso or the painting substrate. It often appears as a matrix of cracks on the upper surface and when severe it can be quite disfiguring and hazardous to the stability of the paint.

Before

In Progress (Infills)

The paint layer on Kathleen’s shoes provides a good example of severe crazing. By the time the painting had made it to the studio, the crazing had become so extensive that the shoes were barely holding together. Up close they appeared like little islands of black paint, separated by the harsh swelling and drying process of severe humidity and temperature fluctuations.

The conservation of this artwork was unsurprisingly a long and laboured process. The tears were consolidated and the holes were patched, the painting was cleaned, the aged varnish was removed, the many holes and cracks were painstakingly infilled, the infills were then carefully retouched with new paint, the painting was re-varnished and reframed and finally, the original labels were washed, re-lined to provide them with support and then attached to the back of the painting. The following image reveals the extent of the infills required to fill the gaps that had been created through the crazing of the paint in the shoes alone. All of these infills required delicate placement to not disturb the original paint, followed by accurate retouching to match the surrounding colour.

After

In progress

(Varnish removal)

The entire conservation process took weeks and the end result was a fully and safely restored artwork, refreshed authentically to appear as the artist had originally intended. The before and after photographs reveal a favourable and satisfying outcome.

The work that goes into saving a significantly deteriorated piece such as this requires considerable academic knowledge, precise technical skill and exceptional care and patience. Conserving these pieces is rarely easy, but it is indeed possible. Be rest assured that when your artworks are in the safe hands of a professionally qualified conservator they will be conscientiously conserved to achieve the best possible outcome.

Conservation works by Maïté Le Mens,

Blog by Ella Rimington